The Southern Nevada construction industry for both Higher Education and K-12 is to strive for innovation and efficiencies as it grapples with constrained resources and needs that far exceeds available capital.

BEX recently held its Building the Future of Southern Nevada’s Learning Spaces event which is part of its Leading Market Series. The event was sponsored by CORE Construction and held at The Assembly in Las Vegas.

The event featured Clark County School District’s Chief of Facilities Brandon McLaughlin and the University of Nevada, Las Vegas’ Director of Design, Associate University Architect Patrick Castellano. CORE Construction’s Executive VP Mark Hobaica moderated the event.

This marks the second LMS event organized by NVBEX. Each LMS event focuses on individual sectors to help attendees build their business and obtain a deeper understanding of the local market.

The program allows attendees to build relationships with potential work partners and listen to a discussion of topics surrounding upcoming work and the state of the market. The first LMS in Nevada discussed public works projects and can be read here.

Higher Education

Castellano is part of the UNLV staff that receives project requests in their earliest stages. His team then helps provide cost estimates and builds out a budget to make sense of the economic data related to the proposal.

Once the project moves forward, Castellano will continue to oversee the process and manage any budgetary changes necessary to complete construction.

Higher Education – Funding and Procurement

UNLV uses three sources of funds for its construction projects. These consist of self-funding, donor funding/philanthropy and state funding. Many UNLV projects are relatively small and pop up from individual departments.

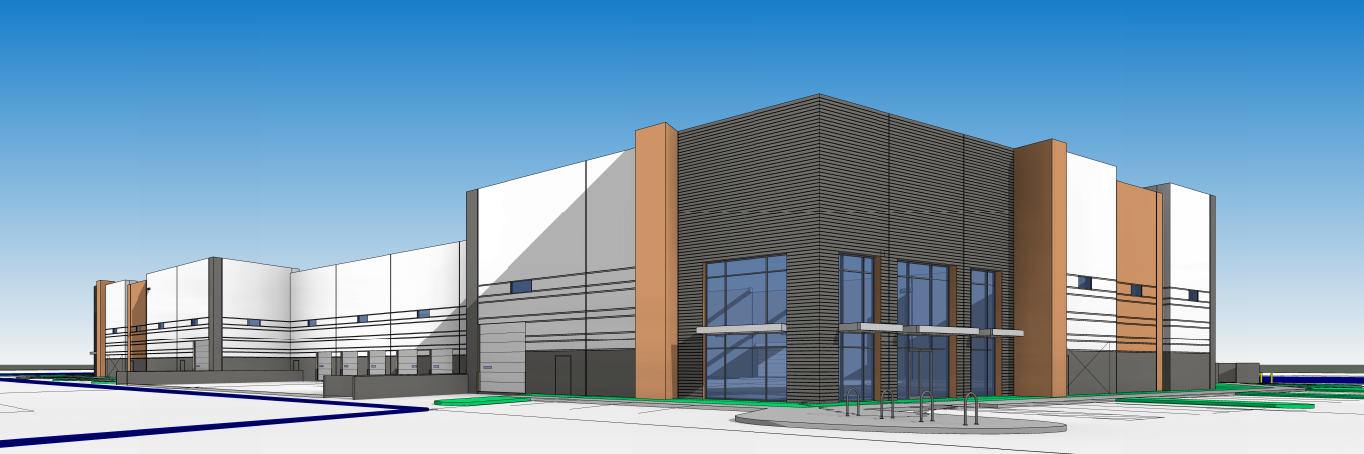

UNLV has made use of a variety of delivery methods for construction contracts. The University has used public-private partnerships on student housing developments in the past and is using a design-build contract for the Brussels Road Parking Garage.

According to Castellano, UNLV prefers Construction Manager at Risk contracts and avoids low-bid contracts. Notably, the University does not have a Job Order Contracting program due to its smaller quantity of projects.

For architectural, engineering, geotechnical planning and special inspections, the University uses a task order services contract. The task order services contract provides the University with a list of parties it can call upon for any sort of work.

The list opens every five-to-six years and will open again in the summer of 2026.

Higher Education Projects

UNLV projects are based on the University’s 10-year master plan. The most recent one was published in 2021.

The Brussels Parking Garage has been awarded to Bomel Construction via a design-build contract. Design work is expected to begin in Q1 2026, and construction is pegged to begin before Q4 of the same year. The fast turn-around is typical of design-build contract.

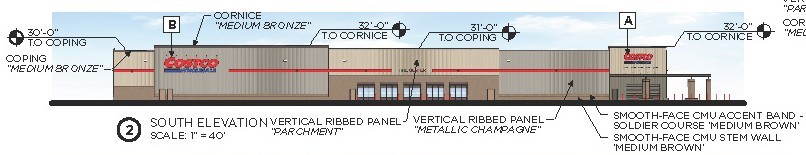

The University’s largest upcoming project is the $135M New Business Building. The State Public Works Division recently awarded a CMAR contract to CORE Construction. The building is being designed by Carpenter Sellers Del Gatto Architects.

While design services are fully appropriated, construction funding for the planned 131KSF facility is expected to be secured during the next legislative session.

In terms of upcoming projects, the University is planning the Harmon Promenade. The promenade is expected to be a pedestrian mall that will become ‘the heart of the campus’. The construction of the promenade will open additional space for new buildings.

The University recently canceled a handful of projects due to leadership changes and shifting priorities. Canceled projects include the ISTB and the Facilities Maintenance Consolidation building.

Higher Education – Approach to Modern Problems

Castellano also spoke on field-related developments that have resulted in less real impacts than some headlines would have us believe. He said recent tariffs have not had a noticeable impact on University-related construction project at this time.

Additionally, UNLV has not utilized AI to assist in the construction process, and Castellano is not inclined to pursue the implementation of Artificial Intelligence.

K-12

Similar to UNLV, CCSD is facing changes in both leadership and its stance toward construction in the modern world. As the Chief of Facilities, McLaughlin is working through a four-part internal change initiative.

The first portion of the internal change is that CCSD wants to “Be the owner of choice.” CCSD intends to improve its internal operations to become a better partner to the A/E/C industry. This is expected to streamline projects, create further demand and improve the lives of students and families.

The second point of the internal change is the standardization of operations across different projects. CCSD has held discussions with past A/E/C partners, in which a common concern was that each project felt like an entirely different experience.

Since these discussions, CCSD has worked on making its procedures consistent across the board.

Along the same lines, the third point of change is ensuring consistency among titles and unifying CCSD leadership. As part of its effort to maintain consistency, the District is focusing on ensuring employees with the same title have similar responsibilities.

The final part of the four-step process is to create an integrated project management platform. This platform will serve the entirety of a project’s lifespan. It will track the project from design to construction. After construction, the software will track warranty, maintenance, providing a centralized place to house records and management.

The new leadership changes in the District have led to a strict focus on student outcomes and experiences. Clark County has one of the lowest daily instruction times in the country at six hours and 11 minutes.

Instruction time is seen as something that should be sacred and protected, to which McLaughlin drew a parallel to project delivery. For example, he said good industry partners will work around the school day, not starting the work until after the instructional day is completed on an occupied campus.

K-12 – Funding and Procurement

CCSD receives funding from the State of Nevada, property taxes, local school support taxes, government services taxes, franchise fees, investments and federal aid. The largest piece of funding comes from bonds. Recently, the State legislature approved the next decade of bond authorization funding for the District.

The last time voters directly approved bond authorization for the district was 1996.

Generally, the District prefers CMAR contracts. CCSD has studied the value of CMAR against low bid contracts and found CMAR has an initial price that is 5.8% higher on average. The project value, however, is 13% higher than low bid projects by the completion of construction.

The State of Nevada is considering implementing other types of delivery methods, such as JOC. McLaughlin said he hopes the State will allow more procurement methods, such as Progressive Design/Build and Integrated Project Delivery.

In recent years, CCSD has increased its utilization of a variety of different architectural firms. McLaughlin intends to make upcoming projects more competitive to design a better-quality product. He said he wants to chase the best idea possible.

Furthermore, in reference to design, he said, “The standard of care is in a delicate place right now.” Improving the overall design quality will allow the District and contractors to move more quickly through the construction phase.

K-12 – Projects

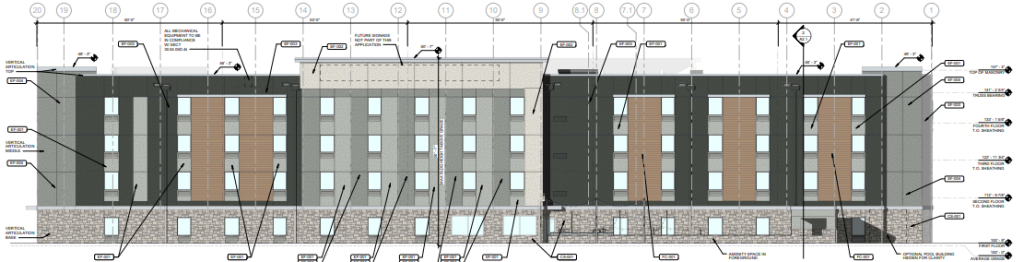

CCSD has been working on a Facilities Master Plan as part of its effort for across-the-board consistency. The District currently owns 442 sites, of which 372 are school campuses.

McLaughlin described a Capital Improvement Plan as the “tactical implementation” of the FMP. CCSD last completed a facilities master plan in 2021.

Many buildings owned by the District are aging, leading to a focus on modernizing assets and renovating existing schools. CCSD currently has $1.2B in shovel-ready projects that are waiting for the conclusion of a one-year pause.

This consists of five middle schools, three elementary schools and a high school.

K-12 – Approach to Modern Problems

Arguably, the most influential issue facing the District is the declining birth rate. As birth rates decline, the District continues to have fewer students to educate. This means there will be less space needed to accommodate students and a reduction in funding.

The District is already seeing the effects of this. The outgoing class of seniors had 21,000 students, while the incoming class of kindergartners only had 17,000 students. CCSD is considering shuttering schools and has turned away from the rapid expansion that characterized the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

McLaughlin said the lower number of students will allow the District to focus more on its overall goal of improving student outcomes and experiences. While there are fewer projects CCSD gets to work on, McLaughlin described them as “cooler.”

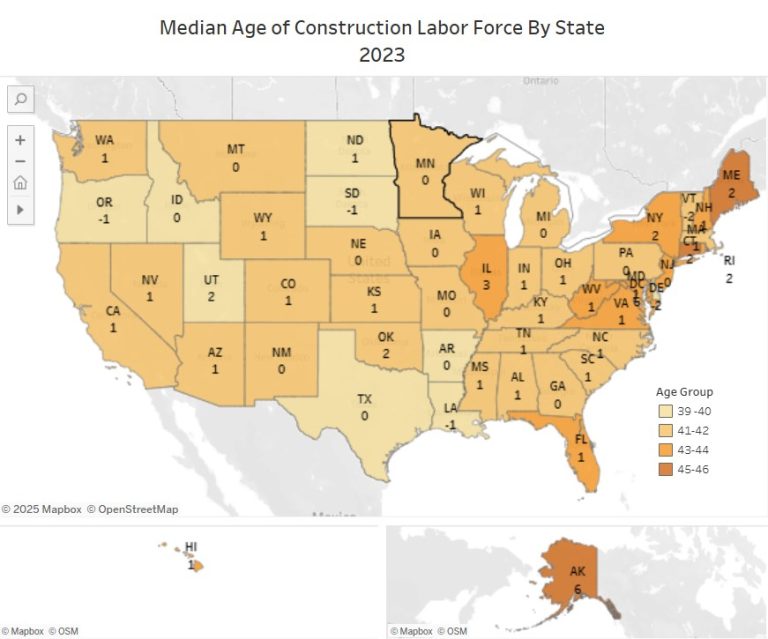

Like Castellano, McLaughlin said the tariffs have yet to have a significant impact on construction costs. However, unlike UNLV, CCSD has experimented with AI in administrative tasks with positive results, and McLaughlin is interested in its implementation from consultants and contractors and would like to capitalize on any innovation it can offer. Additionally, McLaughlin stressed the importance of bringing in and guiding young professionals, as they will be the future generation of the design and construction workforce.